Warning: Undefined variable $post in /var/www/charltons-en/wp-content/themes/divi-charltons-v4/functions.php on line 576

Myanmar

INTRODUCTION TO CHARLTONS

- Charltons is a leading boutique Hong Kong law firm.

- Our focus is on corporate finance and a cornerstone of our firm is our mining and natural resources practice.

- We act for Mine Co.’s, investors, internationally renowned investment banks, private equity firms and global financial advisers to the mining industry

- We have extensive experience in mining sector project – financing and the specific technical agreements required during each stage of a project’s development from exploration to production to mine rehabilitation and closure.

- We advise Hong Kong, PRC and international clients and have been involved in some of the mining sector’s most significant listings, capital market transactions, acquisitions and reverse takeovers in Hong Kong.

- We established a Myanmar arm in 2012 and have advised on mining oil and gas and infrastructure projects

CHALLENGING TIMES FOR THE GLOBAL MINING INDUSTRY

- Global commodity prices remain at historically low levels

- Hoped for recovery has not yet materialised.

- Industry has stalled at the bottom of a ‘super-cycle’

- In 2015, the market capitalisation of the world’s 40 largest Mine Co.’s decreased 37%

- Exploration stage investment decreased 19%.

Signs of Recovery?

- Increase in discovery and project milestone announcements

- Myanmar’s tin production increased 4900% between 2009 and 2014

- Myanmar is now the world’s third largest tin producer

- Recovery in gold prices. Price of gold in Myanmar hit a record high in June 2016

MYANMAR’S MINING POTENTIAL

- Myanmar’s significant mineral wealth remains an attractive investment opportunity for local and international miners and mining-service providers.

- Currently only 5 of the 15 foreign-invested Myanmar mines have reached the production stage

- Positive sector and legislative reforms have not resulted in a significant increase in foreign direct investment (FDI) in Myanmar’s mining sector.

- FDI in Myanmar mining was just US$6.2 million in the year ending 31 March 2016

- The Government has indicated that it intends to privatise remaining state-owned mining operations

MYANMAR 2015 MINES LAW

- Implementing rules yet to be introduced.

- Government can now participate on an equity or profit sharing basis. In principle, this establishes a framework for public-private partnerships (PPPs)

- Where the Government opts to take a share of production it must share the costs of producing an environmental impact assessment (EIA).

- Where the Government opts to take equity, the equity split will be based on the investment amount, the type of mineral, the size and quality of the resource and the estimated costs of production.

- Questions remain as to the Government’s contribution to project costs, cost recovery and project control

- FDI now permitted in small and medium scale projects via JV’s

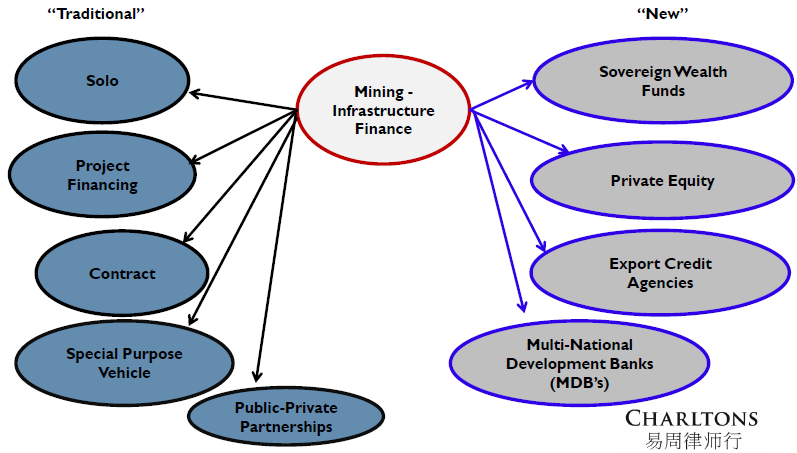

1. MINING INFRASTRUCTURE FINANCING

MYANMAR’S INFRASTRUCTURE CHALLENGE

- Myanmar lacks some of the basic infrastructure necessary to attract whole scale mine development

- Only 38.9% of Myanmar’s road network is paved and road density is among the lowest in South East Asia

- Many of Myanmar’s mineral deposits are located in remote, poorly explored yet highly prospective regions.

- Lack of available rail, port and other critical infrastructure represents a major obstacle to developing many of Myanmar’s most significant mineral deposits

- Inadequate infrastructure affects mine capacity and output as well as safety

- Urgent need to develop adequate refining, processing and storage facilities

- Myanmar Government understands it must play a key role in infrastructure development but there remains lack of planning in respect to public financial intervention as part of private sector led initiatives

- No cross-sector, cross-ministry plan prioritising infrastructure projects that contribute to social and economic development.

- Historically the Government has favoured PPPs in respect to road development. Over 60 build-operate-transfer (BOT) concessions awarded since 1996. However, numerous instances of PPPs implemented based on unregulated, ad-hoc decisions.

- Challenge is to ensure mining infrastructure is integrated into country’s existing and future infrastructure network

- Mining infrastructure will benefit Myanmar’s agricultural and other sectors

- Mining-infrastructure development can be a tool in the ‘formalisation’ of Myanmar’s illegal and small-scale mining sector

MINING INFRASTRUCTURE FINANCING

- Infrastructure development is a significant requirement for the success of a mining operation

- Increasingly difficulty to independently finance, operate and manage projects with large scale infrastructure requirements

- Major Mine Co.’s, such as BHP and Rio Tinto are capable of building and operating their own infrastructure. However, this is not feasible for the vast majority of companies operating in the sector.

- To be beneficial for a country’s development, non-renewable resource extraction should be leveraged to build long-term assets, such as infrastructure, that will support sustainable and inclusive growth

- Cost of infrastructure required is a multiple of that required to carry out exploration and construct mineral extraction and processing facilities.

- A lack of mining-infrastructure limits exploration targets

SOURCES AND FORMS OF MINING INFRASTRUCTURE FINANCING

Government / Public

- Governments can facilitate and incentivize private infrastructure investments in various ways through the use of financial leveraging tools such as guarantees, insurance policies, credit enhancements (e.g. the European Project Bond Initiative), grants, tax exemptions and other fiscal incentives,

- The public sector can set up or co-invest in fund vehicles, e.g. a national or regional infrastructure fund.

SPVs

- An investors, finance, construct, own and operate the infrastructure asset through an independent financing vehicle (SPV).

- The SPV makes all decisions regarding access and negotiates with Mine Co.’s

Sovereign wealth funds (SWFs)

- State-owned investment funds have lengthy investment horizons

- Funds have their origin in currency deposits, pension investments, central banks, fiscal surpluses

- Singaporean and Qatari sovereign wealth funds engaging the mining sector as project investment partners

MDBs and regional organisations

- Sovereign concessional loans from MDBs and other international development finance institutions are an increasingly popular form of mining infrastructure financing

- MDBs can play an important role as catalysts for private investments in various ways such as advising on mining project design, attracting co-investors, and providing insurance

MDBs AND REGIONAL ORGANISATIONS

MINING INFRASTRUCTURE FINANCING: OPEN ACCESS VERSUS PRIVATE OWNERSHIP

Independent Model

- Mine Co. maintains operational control over infrastructure.

- Mine Co. can avoid disruptions, delays and additional repair and maintenance costs, and have flexibility to deal with breakdowns and force majeure events.

- Private ownership encourages competition and first mover advantage

Public Access / Shared Use Model

- Creates a structural barrier to monopolistic behaviour

- ‘Non-rivalous’ until capacity has been reached

- Perception that costs imposed by regulations create economic inefficiencies and market distortions

- Excess regulation can be a disincentive to investment

- Economies of scale and lower marginal costs can lead to increased profitability

TRADITIONAL APPROACHES TO MINE FINANCING

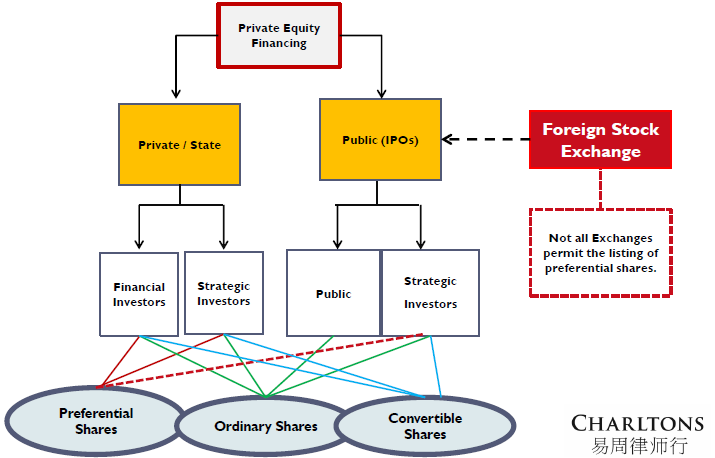

FORMS AND SOURCES OF PRIVATE EQUITY MINING FINANCE: EQUITY

EQUITY

- The raising of finance at the exploration stage of a mining project will invariably involve equity.

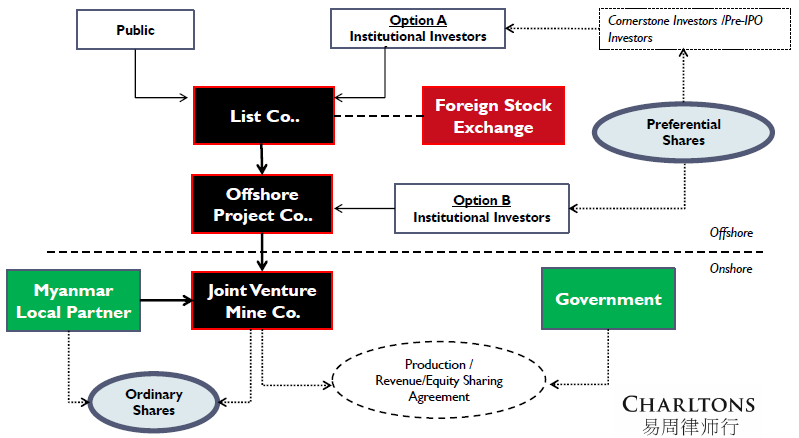

- JV investment model adopted in Myanmar restricts the forms of equity capital raising available to Mine Co.’s onshore in Myanmar

- Greater flexibility may help mobilize a new class of mining investors, especially at the local level

Preference shares

- Benefits for both companies and investors.

- Typically have a fixed dividend that must be paid before any dividends can be paid to ordinary shareholders.

- Some types of preference shares (cumulative shares) allow for the accumulation of unpaid dividends.

Options

- Viability of options as a method of capital raising for Mine Co.’s depends largely on how lucrative a project proves itself to be

- Post initial equity phase and project is established as bankable

- Attractive to investors when a ‘bankable’ project is about to commence additional drilling

- Attractive as the market recovers and investors become more optimistic

- ‘Share-option’ can be utilised as part of corporate (or Government-authored) benefit sharing schemes

IPOs

- Mine Co.’s with assets in developing countries will often list on an overseas exchange because:-

- there is likely to be wider access to investors, and

- there may not be a viable stock market in their host country.

- YSX not yet a viable exchange for mining capital raising, but there is no reason it cannot be developed with a focus on the mining sector

- Overseas exchanges demand high corporate governance standards, which companies in Myanmar could find hard to meet

- In the current ‘super-cycle’ capital markets have proven to be highly risk-averse in respect of mining stocks

- Equity raised by the global junior mining and metals sector has fallen year-on-year since 2012

OVERSEAS EXCHANGES

PROPORTION OF MINERALS COMPANIES ON SELECT GLOBAL STOCK EXCHANGES

| Exchange | % Minerals Companies of Total Market Capitalisation |

| ASX | 16.9% |

| LSE | 6.3% |

| HKEX | 3.5% |

| SGX | 0.5% |

Source: Bloomberg; September 2015

TYPICAL ‘OFFSHORE’ IPO STRUCTURE

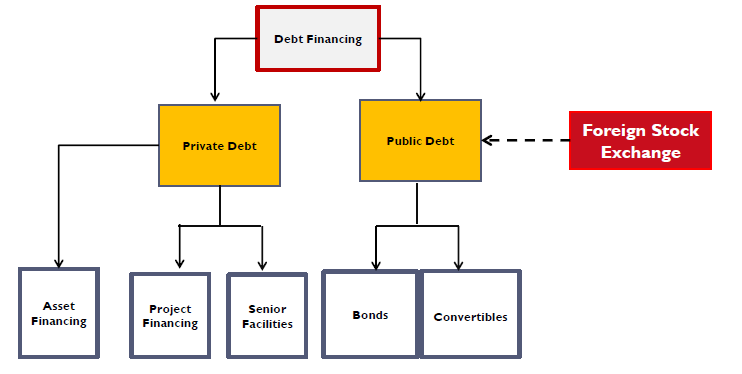

DEBT

- Secured debt holders bear less risk than holders of equity

- Typically not available until a project is ‘bankable’ (once a feasibility study has been produced).

- Lack of credit facilities for mid-level/smaller producers looking for debt financing to support the development of new projects

- Convertible Bonds not available at the Myanmar JV level.

- Debt is less expensive than project financing as a lender assumes less risk (unless a lender views a single project as less risky than the borrower’s entire portfolio of assets).

- There is very little experience of project finance in Myanmar

- Foreign borrowing is permitted, but subject to approvals from the MIC and the Central Bank.

- MIC must approve the proposed debt to equity ratio. There are no limits on the debt to equity ratio but 70:30 is generally preferred by MIC.

- Practical experience of implementation and enforcement of security arrangements is limited in Myanmar.

- While there are a number of types of security interests available in theory, some are uncommon in practice and remain largely untested

FORMS AND SOURCES OF DEBT MINE FINANCING

DEBT SECURITY IN MYANMAR

- In theory it is possible to take security over shares, land, buildings and bank accounts in Myanmar.

- The approval of the MIC is required for the grant of all forms of security.

Security over shares

- Myanmar law permits the creation of equitable mortgages and pledges.

- An equitable mortgage and pledge must be registered with the CRO within 21 days.

Security over bank accounts

- Security can be created over a bank account of an FIL incorporated JV Co. Questions remain as to enforceability.

Security over land and building

- FIL Co. may charge/mortgage long-term leases, subject to MIC approval.

- The consent of the lessor/property owner is also required, (or Government department if land is State-owned)

- FIL Co.’s can lease land for up to 50 years, with option to extend by two additional terms of 10 years each. Leases of more than fifty years are available in less developed regions of Myanmar.

Assignment of contractual rights

- Assignment of the rights and obligations under all relevant project contracts, including leases, can be made.

3. ALTERNATIVE APPROACHES TO MINE FINANCING

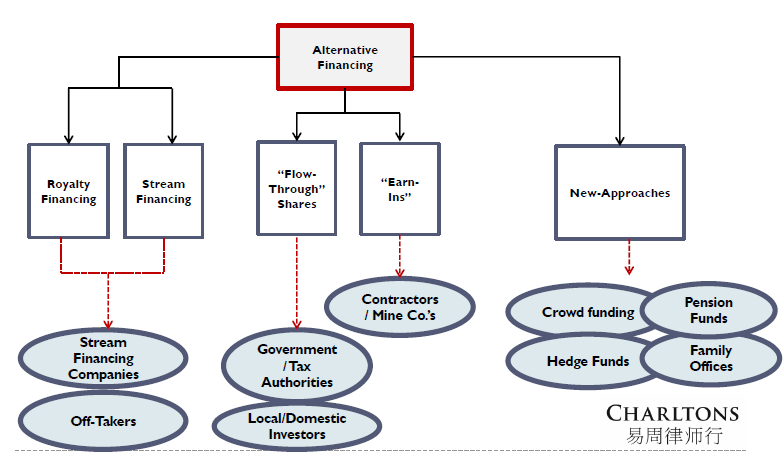

FORMS AND SOURCES OF ALTERNATIVE MINE-FINANCING

ALTERNATIVE FINANCING METHODS

- Junior and exploration stage Mine Co.’s are struggling to find financing, even for strong projects

- Miners are increasingly relying on alternative financing methods to secure the finance needed to bring their projects to production.

- Alternative methods of capital raising capital are attractive when market conditions make equity financings very dilutive and debt financing difficult and expensive to obtain

ALTERNATIVE FINANCING: ROYALTY FINANCING

- Overlooked alternative for small to mid-cap Mine Co.’s to raise funds.

- Appropriate when indicated reserves are in place and bridge financing is needed to complete further exploration and development work and to produce a “bankable” feasibility study.

- Mine Co. sells a percentage of its future revenues to investor

Advantages

- Mine Co. retains clear control of operations

- No onerous financial covenants

- No surrender of board seats

- No dilution

- Less of a ‘front-end’ burden compared to debt products

ALTERNATIVE FINANCING: STREAM FINANCING

- Stream Co. pays a deposit in exchange for a portion of a mine’s future output.

- Some streaming arrangements involve a deposit.

- Deposit can be for specific purposes or alternatively Mine Co. can utilise deposit as it sees fit.

- Deposit may be characterized as ‘deferred revenue’ rather than debt for accounting purposes.

- Stream Co. can also make additional payments on delivery

- Possibility of product ‘buy-back option’. Protects Mine Co. in the event of a shortfall in production.

- A stream sees its full value returned over the life of the mine

- Due diligence requirements for alternative finance differ from those of a pure equity and debt raising – detailed information about a project’s life of mine models and geological mapping are required

- A streaming transaction may also be seen by the market as an endorsement

ALTERNATIVE FINANCING: “EARN-INS”

- Under an ‘earn-in’ or a ‘farm-in agreement’ a contractor (or a person as the case may be) acquires an interest in (but not full ownership of) a mining tenement by carrying out exploration work, or contributing a proportionate part of the cost of exploration work to be carried out.

- Investing partner commits to incur a minimum fixed expenditure over an agreed time period – often with the right to spend further at its own election or the obligation to incur further outlay if certain targets are achieved – in order to earn a pre-determined share of ownership

- Earn-in agreements featuring staged entry allow the partner to reduce the upfront commitment to entirely greenfield prospects while retaining the option to secure control if initial exploration proves successful.